The Conley and Eddy Family Migration to Kansas onto Indian Land in the 1860's

The history will contrast the Potawatomi

Indians and the Osage Indians up to the time when lands were ceded and the

relationship between these events and my family coming to

Kansas.

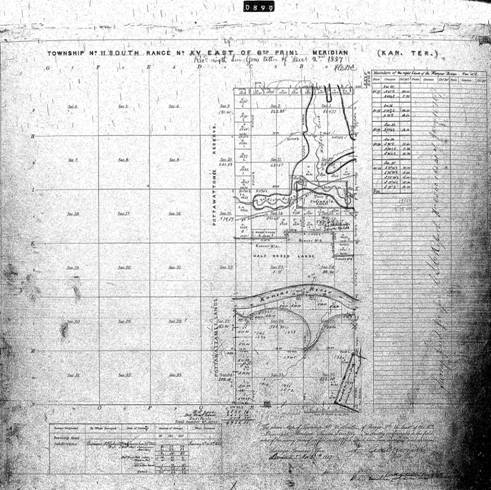

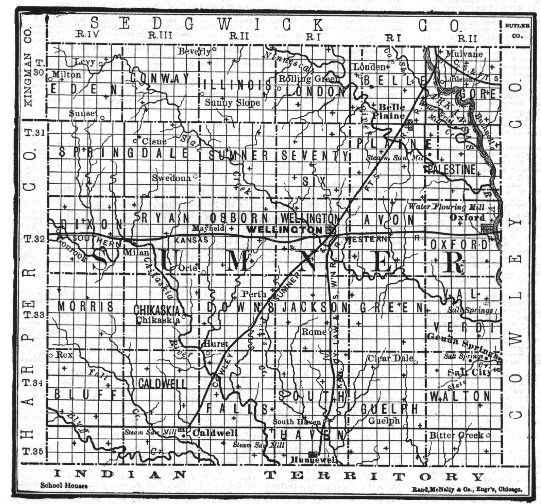

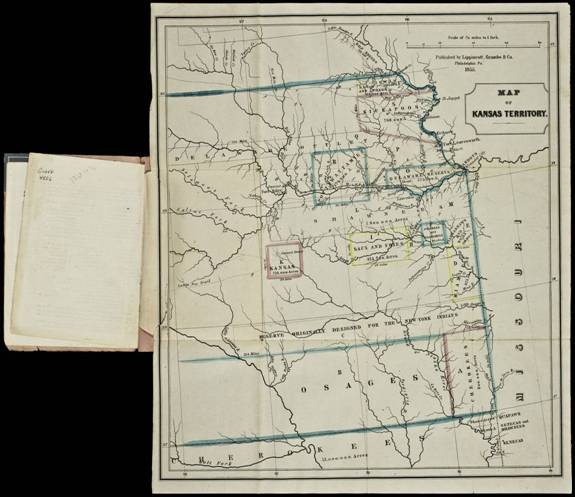

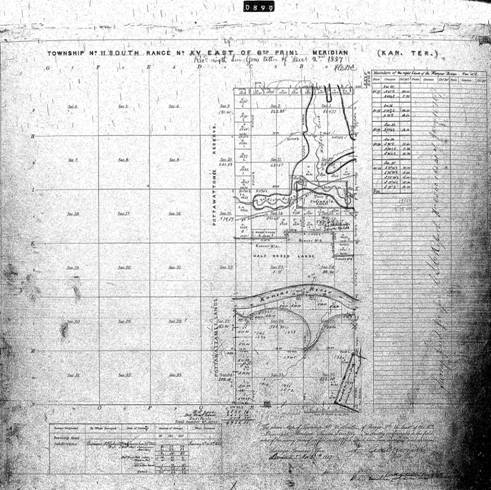

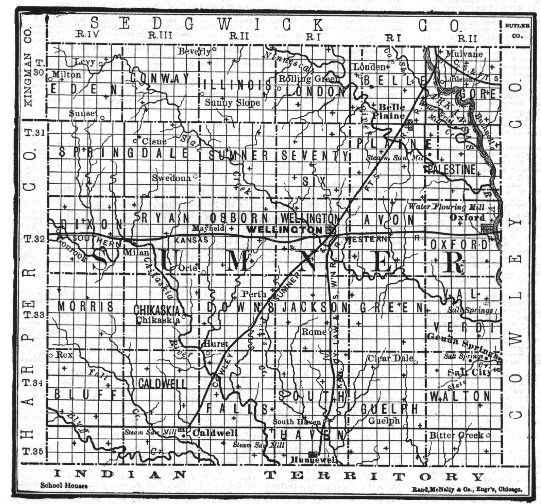

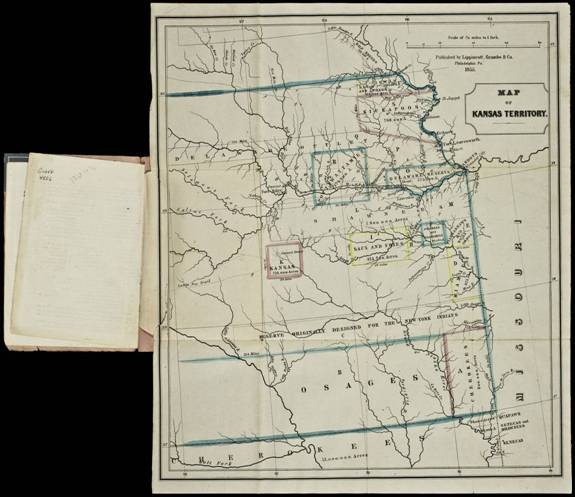

Figure 1 and 2 are from the 1855 History of Kansas and describes the

Osage land as a strip 50 miles wide and 165 miles long. The Potawatomi land in Kansas was an area 30 miles square and was

ceded very soon after 1855. My father’s

family, the Conley’s, migrated to Osage Trust lands and my mother’s family the

Eddy’s migrated to Potawatomi reservation land (figures 3 through 7). The names of the owners were ‘Wahunsonacock’

which is a Powhatan Indian name. The reservation was Potawatomi. The paper is the comparison between the Potawatomi

Indians and the Osage Indians culture. The paper refers to contemporary political

boundaries rather than state the obvious that they were future Kansas counties or

states at the time of Indian migration.

Figure 1: Map showing

Indian

Land

in 1855, the period just prior to

when my ancestors came to

Kansas

figure 2 describes the map

figure 2 describes the map

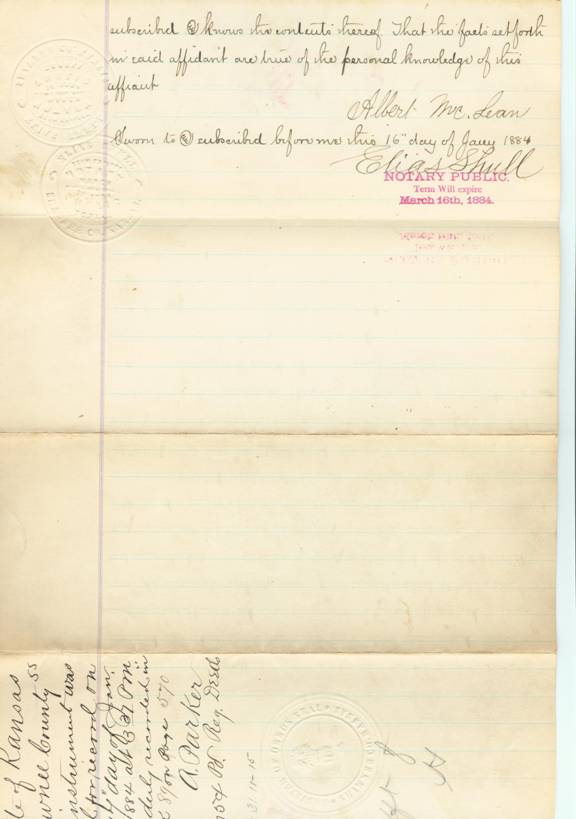

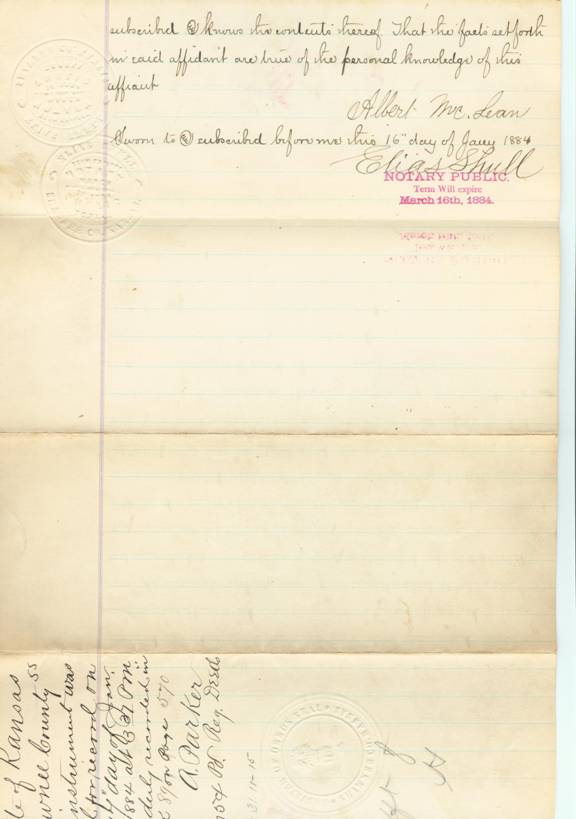

Figure 3: section 31 Land sold by Joseph Negahnquet

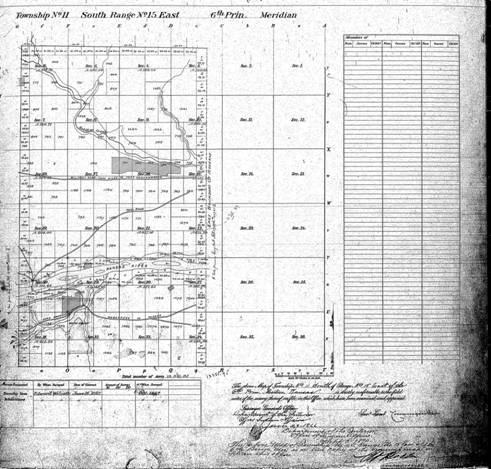

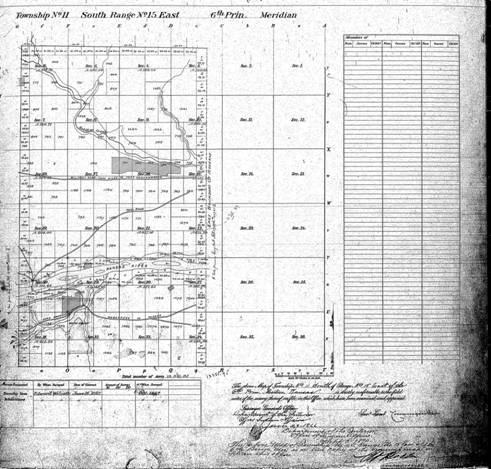

Figure 4: The

Topeka

land a little later.

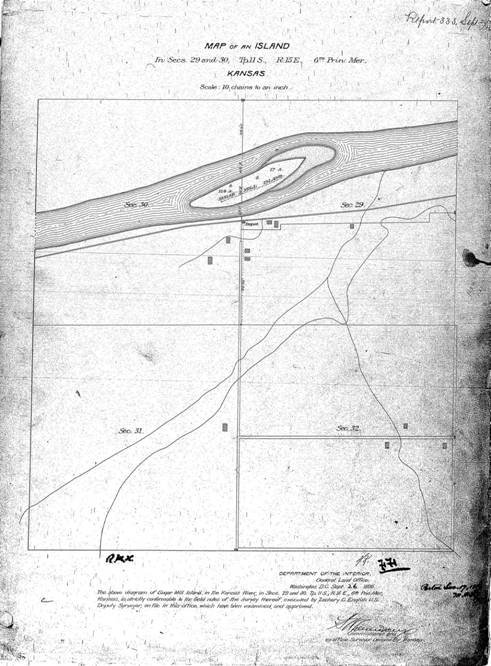

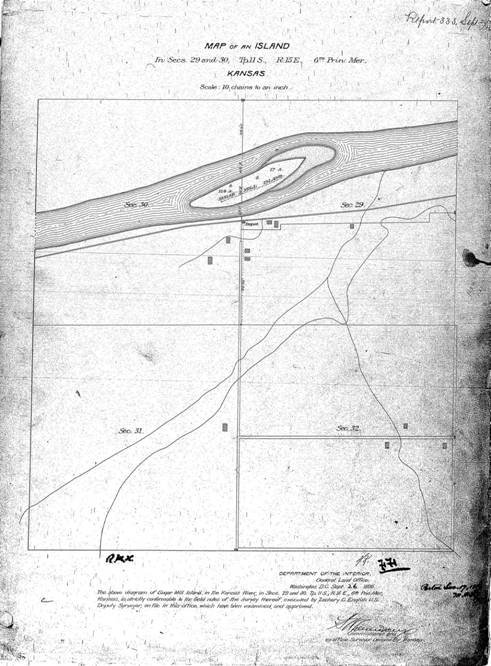

Figure 5: This shows the house on the NE corner of Section

31.

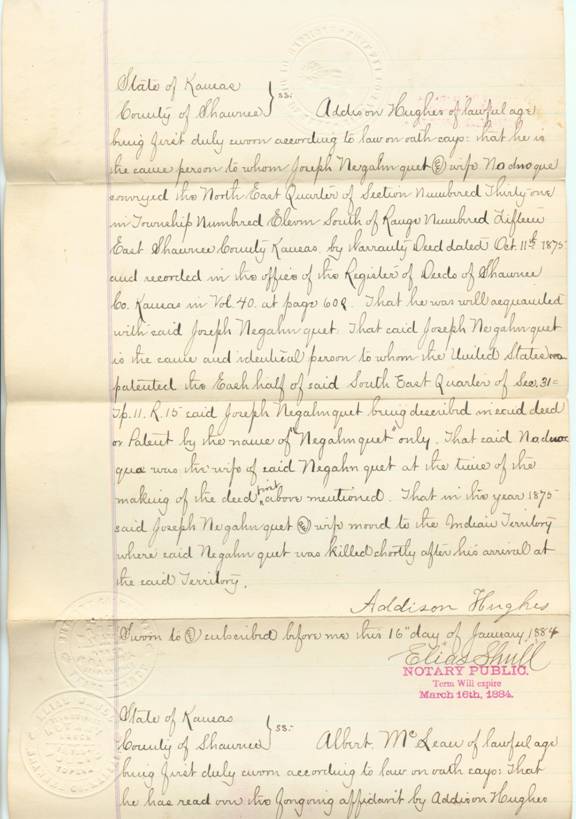

Figure 6: Patent for the

Topeka

land

Figure 7 patent for

the land.

Language: The Potawatomi are

Algonquian speakers. Their language

family covers upper eastern North America. The language is closely related to Powhatan, Ojibwa

and Ottawa. They understand each other, like we

understand Cockney in England. The name of the Potawatomi tribe means

“Keepers of the sacred fire” in Ojibwa.

The Potawatomi call themselves ‘Neshnabek’ (original people) in their

language.

The Osage are Siouan speakers. The Siouan language was ‘Dhegiha’ spoken by the

Kansa, Omaha,

Ponca, Osage and Quapaw.

Dwellings: The Potawatomi lived in villages near rivers or

lakes. Their permanent villages were made

up of rectangular buildings of poles covered by cedar or elm bark. The buildings had a high arched roof. In the summer the living space for smaller

encampments was made up of oval, domed wigwams with saplings and covered with elm

bark or woven cattail mats. The holes in

the roof were made for the smoke to escape in both cases. Cooking shelters were separate. Menstruating women were isolated in smaller

structures also.

The Osage had permanent villages

for most of the year. Sometimes they

built lodges for their permanent villages.

The living space of the Osage was a wigwam covered with bark mats or

hides. The Osage lived in rectangular

bark covered wigwams. Small circular

lodges were less common. The Osage

hunting shelter was a tent with four poles in a rectangular pattern.

Subsistence: Potawatomi subsistence patterns depended on the season. They fished with hooks, lines, harpoons,

traps and weirs. They hunted beaver

raccoon, squirrel, opossum and elk or moose, bear and buffalo. Basically they hunted any game. Later the Potawatomi raised corn, peas, beans

pumpkins, squash and melons. Like many

Indians they grew tobacco for ceremonial purposes. The last buffalo hunt was legend. The Potawatomi were anticipating a long, cold

winter. Since buffalo were an important food source, preparations were made for

a hunt. The Potawatomi were good at curing and drying buffalo meat. They were skilled at making buffalo hides

into blankets. Federal regulations of

the 1840s required the Potawatomi to get permits from the Indian agent before

leaving the reservation. With a hunting permit the Potawatomi hunting party

traveled west in Kansas

to search for the buffalo. The party’s horseback journey took them through

towns of Junction City, Lindsborg, Great Bend and Wakeeney,

before finally locating a buffalo herd. There, the Potawatomi hunting party

took enough buffalo to satisfy their needs.

This was their last hunt of the buffalo.

For the Osage, Hunting was the

primary subsistence activity but they did grow some corn, beans and squash and

dried and stored it. The Osage

farmed. Cattle had been provided by the

US Government in order to alter the Osage culture and it did not work. The Osage killed and ate livestock provided

by the US

government. Trade was critical to the

Osage. After European contact they

depended on the French for guns and metal objects. The Osage did what they could to keep the

Caddoan’s from trading with the French for guns. In the early 19th century the

Osage adopted European tools. (Volume 13

“Plains” p 478). Most Osage artifacts

found are from the French trading period.

They adapted to European tools quickly.

The Osage, in their migration, may have been exposed to the Oneota based

on early artifacts found in Osage sites. (Volume 13 “Plains” p 476)

Religion: The Potawatomi did

not have a structured religion early in history. The Potawatomi felt a part of all

creation. (Gale Volume 1: P258) They went on vision quests and had medicine

bundles. They did adopt religion later

like the ‘Dream dance’ or ‘drum cult’.

They tried the peyote cult in later years. Their Christianity still has elements that

balance between nature and humanity. The

Potawatomi believed that there are two spirits who govern the world. One is called ‘Kitchemonedo’, the Great

Spirit and the other ‘Matchemonedo’, the Evil Spirit. The first is good and beneficent. In former times the Potawatomi worshiped the

sun, they sometimes offered sacrifice to the sun in order to cure the sick or in

order to obtain something. The Potawatomi would hold what was called the

"feast of dreams”. Dog meat was used at this feast. Burial was probably underground, though there

is evidence that placing the body on a scaffold was practiced (Gale Volume 1:

P258).

Osage Controlling power was called

“Wakanda”. There were 24 paternal clans

and each had a ‘life symbol’ sacred bundle.

The village plan followed their idea of the universe. The Osage lived in

a Moiety with ‘Tsizhu’ (North) and ‘Honga’ (South). One Moiety came to the earth from the sky. Osage kinship was of the Omaha Indian type. That is that the Mother and Mother’s sister

were called mother. It also meant that

the Father and Father’s brothers were called father. The Osage participated in the Peyote

ritual. The Osage chief Black Dog (whose

namesake trail is famous for traversing the lower part of Kansas)

had a Peyote altar near Hominy, Oklahoma

(Volume 13 “Plains”: p480).

Political organization / Customs:

Potawatomi organization

centered on Clan membership. Each clan

has an origin myth and related to an animal.

They guard the sacred bundle.

Clan chants were all different.

Songs and dances bestowed names. Naming practices are very important to

the Potawatomi. This was like secret

societies.

Osage organization was built around

a Moiety. Each Moiety chief had equal

authority. Hereditary chiefs were

replaced with War chiefs. Warfare was

put under the ‘Little Old Men’ who could recite the words Life cycle

polygamy. The post marital residence

moved from the father’s family to the mother’s family (Volume 13 “Plains” p

478).

Treaties: The Potawatomi were originally located around the

southern portions of Lake Michigan, in southern Wisconsin,

northern Illinois

and northwestern Indiana. After removal of Indians from Michigan, Indiana, Illinois and Wisconsin,

most Potawatomi moves until they settled on the reservation in northeastern Kansas (figure 1). They like most Indians were moved west of the

Mississippi.

Some of the Potawatomi went to Southwestern Ontario.

(Kehoe, p 303) Following 1833, most of

the Potawatomi people were moved from the tribe's lands. Many died on the

trip to the new lands through Iowa, Kansas and Oklahoma.

Under the Indian Removal Act, the Potawatomi were

relocated west, to Missouri in the mid-1830s and then to Council Bluff, Iowa in the 1840s. After

1846, the tribe moved to Kansas

.

The reservation was thirty square miles which included part of present-day Topeka

(figure 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5). This is discussed

later in regard to the affidavit for land my Mother’s Grandmother’s family that

settled just west of

Topeka. It was called Indian Hill Farm. One can see it was on west Wannamaker road. The farm’s hill was flattened for development

about 12 years ago, but the hill was a source of Indian artifacts.

The Potawatomi tribe originated around the Great Lakes. The tribe was living off the resources of

the Great Lakes. Anything else they needed they acquired

through trade with other tribes. During

this time the Potawatomi held no real concept of land ownership. Their beliefs

taught them that land belonged to all living things. The U.S. Government, in

its first treaties with the Indians, established boundaries for tribal land. In

the treaties that followed the Potawatomi agreed to sell land to the

Government. Those concessions led to more loss of land.

The 1830 Removal Act was policy of the United States government. The

policy revolved around a dream that the Indian "problem" could be

eliminated by persuading the eastern Indians to exchange their lands for

territory west of the Mississippi.

The exchange would leave the area between the Appalachians and the Mississippi river free for white settlement.

During this migration west, the Potawatomi made stops in Platte Country Missouri

in the mid-1830s and Council Bluffs,

Iowa in the 1840s. The tribe

controlled millions of acres at both locations. After 1846 the tribe moved to

present-day Kansas, the "Great American

Desert." The area

lacked the resources of the Great Lakes, the political

reality of the removal left the tribe no choice. It amounted to a period of

adjustment for the tribe, just like so many times in the past. At that time,

the reservation was thirty square miles which included part of present-day Topeka.

Settlement changed with the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. Opening

this territory to settlement started immigrating white settlers. The settlers

moved onto Indian lands. It was called

"squatter sovereignty." Additional white migration to Santa Fe and Oregon areas

made land like the Kansas

Territory suddenly very

appealing.

Two treaties cut the reservation into portions that accommodated individual

interests. The railroad received over 338,000 acres, Jesuit interests 320

acres, Baptist interests 320 acres, and the rest was divided into separate

plots. The Jesuits, failed to make Kansas a

center of Catholic activity around St. Mary's Mission.

Congress passed the Dawes Act (the General Allotment Act) of 1887. Congress

said they could no longer protect Indian lands from further settlement and the

demands of the railroads and other enterprises. The basic premise of the

General Allotment Act was to give each Indian a private plot of land on which

to become an industrious farmer. To hasten assimilation, the law provided for

the end of tribal relationships, such as land held in common. It stipulated

that reservations were to be surrendered and divided into family-sized farms of

160 acres for each male and smaller portions for other people which would be

allotted to each Indian. The aim was to substitute white culture for tribal

culture.

The Potawatomi refused to recognize their allotments of land or the right of

the government to make changes. The government withheld federal payments due

the Potawatomi Prairie Band and gave double allotments of the tribes land to

whites, Indians from other tribes, and the agent's relatives. Much of the allotted

land was too poor to farm, and the tribe received no financial credit and was

given little help of any kind.

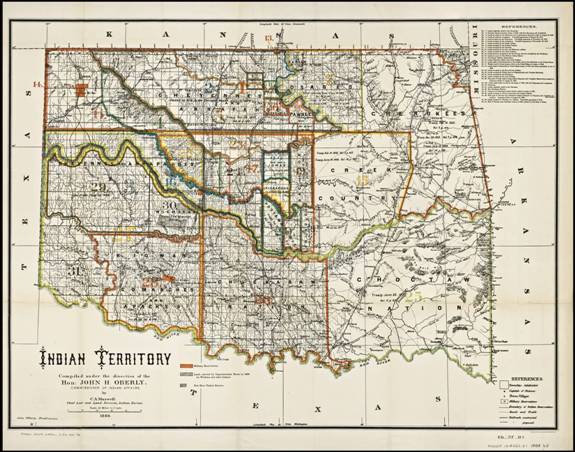

The Osage began treaty-making with

the United States in 1808,

by the Osage Treaty and their first cession of

lands in Missouri. The1808 treaty also provided for approval by

the U.S. President for future land sales and cessions. In 1808 the Osage moved

from their homelands on the Osage River to western Missouri. Part of the tribe had moved to the

Three-Forks region of Oklahoma

soon after the arrival of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The Civil war slowed settler’s

interest in moving the Osage from reservations, but after the war those lands

were ceded.

Between the first treaty and 1825, the Osages ceded

their traditional land in Missouri, Arkansas, and Oklahoma

to the US

in the treaties of 1818 and 1825. They were to receive reservation lands and

supplies to help them farm and lose their native culture. They were first moved

onto a southeast Kansas reservation called the

“Osage Diminished Reserve”,

(Independence, Kansas). As stated earlier the first Osage reservation

was a 50 by 150-mile strip (figure 1). White squatters were a problem for the

Osage. Subsequent treaties and laws through the 1860s reduced the lands of the

Osage. By a treaty in 1865 they ceded more land and faced eventual removal from

Kansas to Indian

Territory.

The Drum Creek Treaty passed by Congress July 15,

1870 was ratified by the Osage in Montgomery

County, Kansas on

September 10, 1870. The treaty provided that the remainder of Osage land in Kansas be sold and used to relocate the Osage to Indian Territory. The Osage benefited by the change in Washington administration. The Osage sold their land to the

administration of President Grant. They

received $1.25 an acre rather than the 19 cents previously offered to them by

the US

and given to other tribes. The Osage

occupied land in present-day Kansas and in

Indian Territory which the US

government promised to the Cherokee and four other tribes. When the Cherokee

arrived to find that the land was already occupied, many conflicts arose with

the Osage over territory and resources (figure 1).

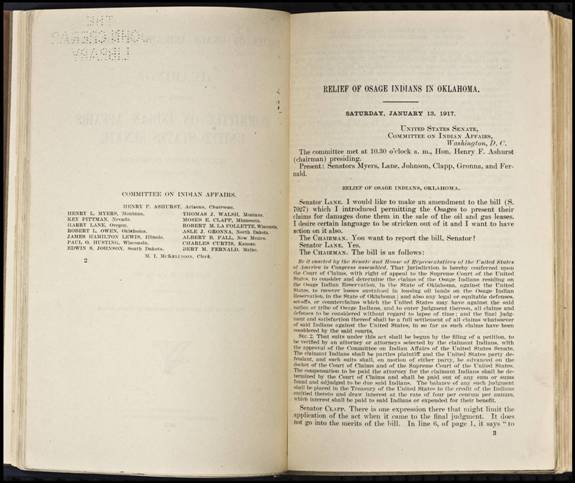

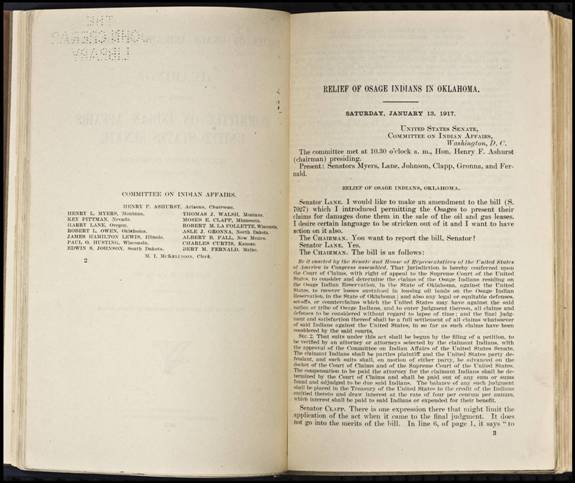

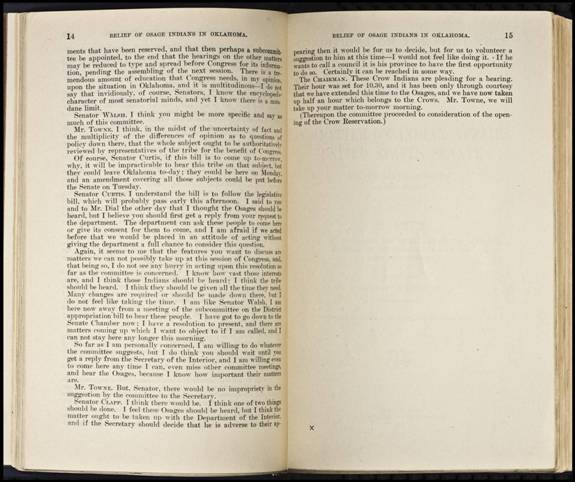

The Osage bought their own reservation, and they

retained rights to the tribes land and sovereignty as a result. Their reservation is Osage county Oklahoma in

the north-central portion of the state between Tulsa

and Ponca City. Life was hard on the Oklahoma

reservation as described in 1917 when Congress met to help with the relief of

the Osage in Oklahoma. Senator Charles Curtis from Kansas was part of that committee. The agent J George Wright had not even been

on the reservation and all of his activity favored oil and gas companies

developing the land. Part of the relief

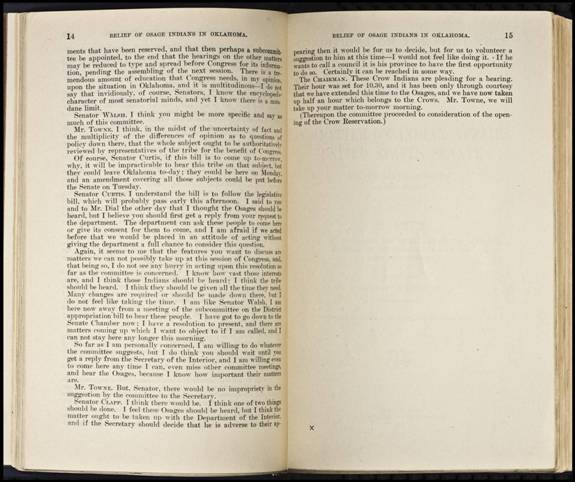

was to provide money for the use of the resources (figure 12 and 13 showing parts

of the congressional record).

Figure 12

congressional record of Relief of the Osage Indians

Figure 13 showing

Kansas Sen. Curtis was interested in relief of the Osage and there was pressure

to move on to the next tribe in 1917

Conclusion: The significance of this comparison is that the two

tribes spoke different language but shared a number of common traits in their

culture due to their similar life ways.

My Family

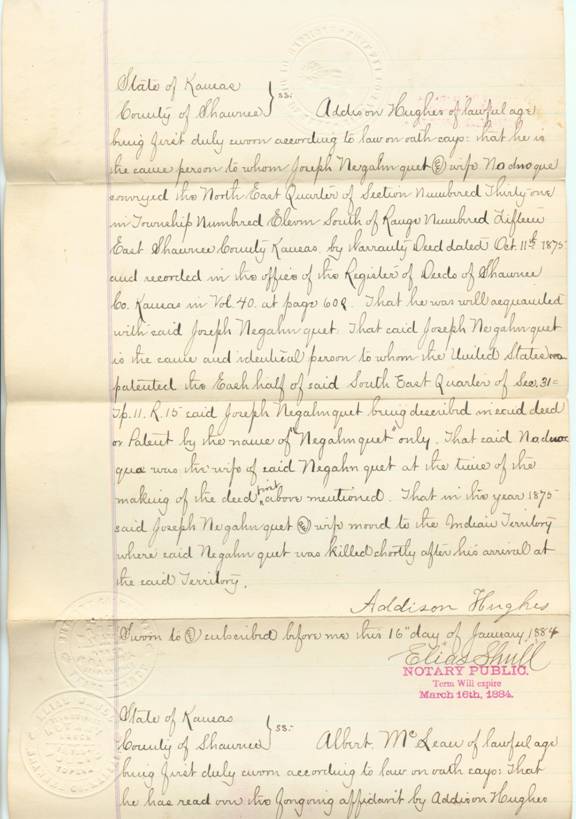

link to Tribal Land: Potawatomi On my mother’s

side the Eddy family Property was transferred from an Addison Hughes. The

Potawatomi controlled millions of acres. After 1846, the tribe moved to Kansas. At that time,

the reservation was thirty square miles which included part of present-day Topeka (figure 1). Addison Hughes obtained land that was part of

the reservation from Joseph Negahnquet and his wife Nodnoque. It was defined as the NE quarter of section

number 31 in township number 11 south of range number Fifteen East Shawnee county Kansas by warranty deed

Oct 11, 1875 (figure 3, 4 and 5). Joseph

Nequahnquet moved to Indian Territory and he was killed shortly after his

arrival in Oklahoma.

This is in relation to the documents

for land my Mothers Mother’s family settled just west of Topeka they called ‘Indian Hill Farm’ that

was on west Wannamaker road. The farm

and hill was razed for development about 12 years ago, but was a source of

Indian artifacts for the family for years.

The Eddy

property on Potawatomie reservation was bought from a Negahnquet. Interestingly there was an Albert Negahnquet,

who was Potawatomi, the first full-blood Indian of the United States

to be ordained a Catholic priest. Born near St Marys, Kansas, in 1864, he moved with his parents

to the Potawatomi Reservation. (Pottawatomie

County, Oklahoma), From

that point Albert Negahnquet attended a Catholic mission school of the

Benedictine monks. Finally Negahnquet entered the ‘College of the Propaganda

Fide’ in Rome,

and was ordained a priest in 1903. Quite

a change from Indian culture to Catholic priest.

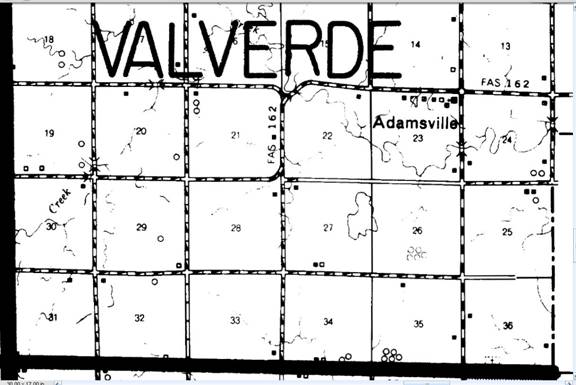

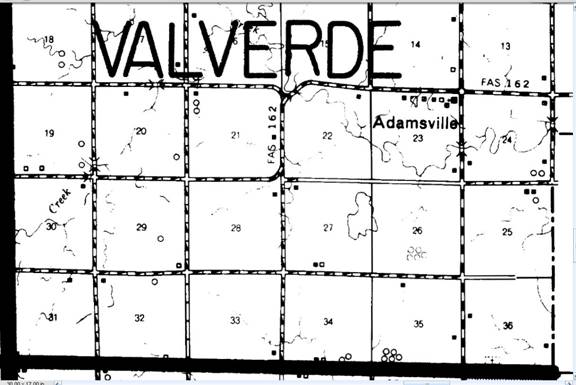

Osage: The Conely (Conley) brothers migrated to Osage Indian trust

lands in 1877. This property described

in detail is in Sumner

County and my Great

Grandfather’s part of it was on Slate Creek. (figures 8 through 10) The three brothers came from Jasper, Illinois but likely they lived in Boone County, Kentucky

in 1877 based on their fathers home at the time of his death which was 1877. Robert M Conely, got Osage Trust land as the South west quarter of

Section 25, Township 33, south of range 2 east,160 acres ,1 Dec 1874. Osage Trust Lands to John C. Conely, was a land grant of the north ½ of the

Northwest quarter and the southeast quarter of the Northeast quarter of Section

26, Township 33, south of Range 2 east, 120 acres, 2 July 1877 (Osage trust

Lands). My Great Grand Father, George Northcutt

Conely, land grant was Lots # 1and #2, and the northwest quarter of the

southeast quarter of Section 25, Township 33, south of range 2 east, 90 acres,

20, February 1877. (Osage Trust Lands) All the land was in Sumner

County, ValVerde Township.

All lands were purchased through the Wichita,

Kansas district land

office. Robert M .Conely came to Kansas

first. Robert came by way of Colorado. George’s Land

grant was before John’s. These farms were less than a mile apart. This gives

more credence that these were the sons of Greenville Connelly (the brothers

changed the spelling at some point). John is stated as having arrived in 1873.

At least we know they are all in Kansas

by the end of 1877. Benjamin is listed with John’s family in the 1880 census.

That’s four of the five sons of Greenville Conely. The three sons of George Northcutt

Conely (my great grandfather) were born in Sumner County. The twins, Oliver and Oscar and definitely

Ira Melvin were born in Sumner

County. Robert’s land and

George’s land are in the same section. George’s land lay near the Arkansas River. John’s was in the next section west. John

moved to be on the River at Gueda Springs Kansas for his Ferryboat business crossing the Arkansas River. We also know in 1880, John is in Bolton Township

Cowley County.

This township is adjacent to the river. In 1884, Robert M Conely is buying lots

in Winfield. George is next located in Walnut

Township, Cowley

County and in 1895 he is in Windsor Township.,

Cowley County (Grand Summit). After selling his land George Northcutt Conely

(Conley) started working for the Santa Fe Railroad and moved to Grand Summit

Kansas which is on the rail road right of way west of Cambridge

Kansas on highway 160 and North on Ferguson Ranch Road

which crosses the railroad twice before getting to Grand Summit 1894 Windsor Township Cowley

County. This substantiates that my family migrated to

Kansas

and

found a home on Indian reservation land from county records research.

Figure 8: Conley Brothers

land from the Osage

Trust. My great grandfather seems to

have bought land with Slate Creek in the middle of it. Great bottom land but flooded. He sold it very quickly and moved to Grand

Summit Kansas.

Figure 9 old county

map of the Conley

Land

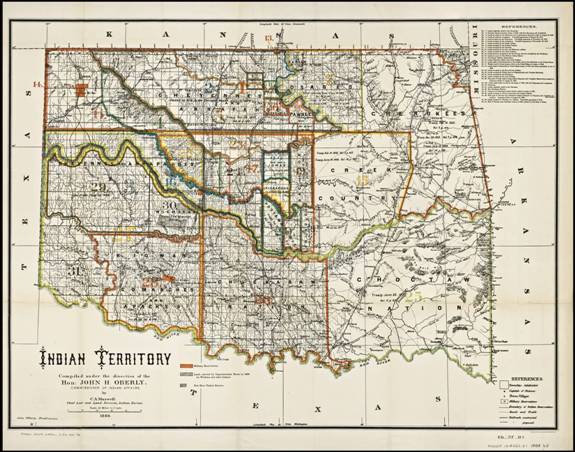

Figure 10: Old Map of the Osage Trust lands that were made

into ‘available’ for purchase.

Figure 11 Indian Territory after the movement of the Osage and

Potawatomi

References:

Chapman, Butler J (1855) “Map of Kansas Territory” to

accompany his history of

Kansas

Bailey, Garrick A. (2001), “Osage”, Handbook of the

American Indian, Volume 13 the “Plains”. Volume 1, 476-496.

Kehoe, Alice B (2006), “North American Indians”, p 303

Malinowski,

Sharon

and Sheets, Anna editors (1998), “Potawatomi”, The Gale Encyclopedia of Native

American Tribes: Volume 1, 256-261

Young, Gloria A. (2001), “Intertribal Religious Movements”,

Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 13 the “Plains”, Volume 2, 996-1010

December 14, 2012

figure 2 describes the map

figure 2 describes the map