These semi sedentary people lived in the Arkansas, Walnut, and Canadian river valleys in proto historic (A.D. 1500-1800) times. They were the Little River focus of the Great Bend Tradition (DeMallie, 2001:548) of the Southern Plains (around AD 1500) based on Spanish accounts. There was a question if the Tawehash may have been related to the Pratt complex or the Bluff Creek complex people who also were semi sedentary planting corn and hunting bison from archaeological evidence in South Central Kansas. C14 show dates as early as 900 – 1000 AD. That precedes the Great Bend Tradition. There is no material evidence that they were the same people as the Wichita. Bluff Creek sites do show evidence of ditches like those found at the Deer Creek site in Oklahoma and at the site near Spanish Fort, Texas that are attributed to the Wichita. It would make a great story, but the Caddo language tends to indicate they came from the Southeast. Pillaert and Wedel say the Little River Focus of Kansas, Washita River Focus of Oklahoma and the Henrietta Focus of Texas are so similar that they could be attributed to a single ethnic group (Bell 1974:36).

The Tawehash raised maize, beans, calabashes, (squash or gourds) (Wedel, 1988:24) watermelons, pumpkins, and tobacco. Bison were a large part of the protein diet of the Tawehash that was supplemented by corn and an occasional Apache, Osage or Tonkawa (DeMallie, 2001:557). They were recorded as having said that they ate Apache’s, which leads to the conclusion that they practiced cannibalism for food or ritual reasons.

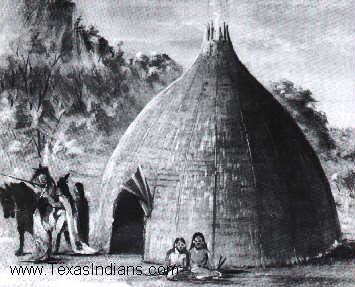

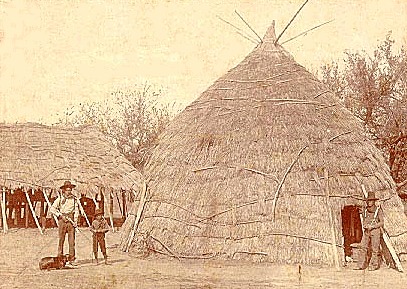

Their grass houses were cone-shaped, with a diameter of 70 to 80 feet (Wedel, 1988:18). The houses were constructed of poles around a circle and drawn together at the top, laced with saplings and then thatched with grass. The flexible poles were then bound across these at regular intervals from the ground to the top. Over this framework long grass was laid in shingle fashion in regular rounds, beginning at the bottom, each round being held in place by light rods. Around the inside were bed-framed platforms of poles that were covered to make beds (Wedel, 1988:19). This house shape gave the casual observer the idea they were haystacks or beehives. The houses had two doors. There was one door on the East and one door on the West. Earlier dwellings had four openings in the cardinal directions.

Their families were Matrilineal in organization and settlement patterns followed. They were living in the middle of their fields until the introduction of the horse when settlements were concentrated and fenced for horses. So they were Matrilineal and practiced cannibalism. It is no wonder they practiced Mother in law avoidance.

The Wichita consisted of three primary bands. They were the Tawakoni, the Tawehash (Taovayas) and to some extent the Keechi. In Texas they add the Waco. Towakoni and Tawehash are the people of Quivira who met Coronado in 1541. The Tawehash guide for Coronado was recorded in the 16th century. Here is an excerpt from “The Journey of Coronado” by Pedro de Castaneda, et al. in the 16th century:

“They followed the river down to the camp, and told the general that in the twenty leagues they had been over they had seen nothing but cows and the sky. There was another native of Quivira with the army, a tattooed Indian named Ysopete. (Winship 1964:235) ….“The governor and Whiskers gave the general a young fellow named Xabe, a native of Quivira who could give them information about the country. This fellow said that there was gold and silver, but not so much of it as the Turk had said. (Winship, 1964:291) …“The general followed his guides until he reached Quivira, which took 49 days' marching, on account of the great detour they had made toward Florida. …... Neither gold nor silver nor any trace of either was found among these people. Their lord wore a copper plate on his neck and prized it highly.” (Winship, 1964:291)

Treviños a released captive confirmed Parrilla’s report of the Tawehash fortification in 1765. According to him it was built to resist Parrilla's Spanish attack. It consisted of a palisaded embankment about 4 feet high, with deep ditches at the east and west ends, to prevent approach on horseback. Inside the enclosure were four subterranean houses for the safety of the people who did not fight (Bell, 1974:356). From early records these people lived in our area prior to 1500 and we know from Coronado’s records from 1541 that the people of Quivera were likely the Tawakoni or the Tawehash.

When Don Juan Onáte, the Spanish Governor of New Mexico, arrived at the confluence of the Walnut and Big Arkansas rivers in 1601, he found a village of 1200 grass houses. It is hard to correlate archaeological materials and the descriptions derived from early European contacts with historic tribes, the fact that these people lived in grass houses suggests that they were the Tawakoni or the Tawehash (Bell, 1974:245). Since the Tawehash built on top of the ground and were clean housekeepers there is little evidence of prehistoric houses of this exact construction to be found. The suggestion has been made that fill marked by wash lines and lenses indicating the fill was accumulated slowly over a period of time instead of a lot of mottled fill (mud covered houses) can be associated with grass covered housed where habitation is indicated (Bell 1974:71).

The Wichita bands shared a Northern Caddoan based language suggesting a Caddoan heritage. (See the attachment on language) Physically the Wichita were darker and larger than most Indians. The Wichita were slightly darker in color than other native plains people (Wedel, 1988:11); the Wichita were distinguished by their tattoos, the scalp lock worn by the men. The women had “faces more in the manner of Moors” (Wedel 1988:11). Although warriors by tradition they tended to be friendly toward strangers and were noted for their hospitality.

The Wichita had acquired horses by 1602 based on the time line in the Columbia Guide to American Indians of the Great Plains (Fowler, 2003:195). The Wichita culture was marked by quick adoption of European ways with the arrival of the French. When traveling the Tawehash lived in Tipi’s covered with hide (in historic time the hide was replaced with lighter sail cloth). Canvas would lighten the weight of a Tipi to be transported by hundreds of pounds. The French traders unlike the Spanish would trade the Indians for horses, guns and domestic trade goods. The Spanish did not give the people horses, guns or anything that could be used against the Spanish in War. The Spanish were allies of the Apache who the Wichita people hated.

The name Wichita was first used in 1719 by the French trader Benard de la Harpe (DeMallie, 2003:196), when he visited villages on the Arkansas River in Oklahoma and called one band the Ouatchitas (Ouatchitas) (Wedel, 1988:6). Variations of that name occurred regularly. Subsequently, in 1835, Americans concluding a treaty with the tribe, referred to them as Witchetaws, from which the current name was derived. The Tawehash were part of this group encountered by La Harpe in 1719. The Bryson-Paddock and Deer Creek site were located on a bluff overlooking the Arkansas River near Newkirk, in north-central Oklahoma near Kaw Lake. It is a Tawehash village from the 1700’s that was visited by French traders. It is one of the earliest Wichita sites that had contact with Europeans. The site contained trash mounds that included metal and glass trade materials plus Wichita artifacts, house patterns, hearths, and pits features. Deer Creek or Bryson-Paddock may have been the mythical “Ferdinandina” in Spanish and French documents and maps (Wedel, 1988:8).

Bryson-Paddock site (34KA5) and Deer Creek show the first evidence of use of the horse by the Wichita in Kay County, Oklahoma. The Wichita obtained Spanish horses from Comanche middlemen and probably through raids on the Apache. However, horse paraphernalia and horse bone have not been previously noted at a known Oklahoma Wichita site. Use of the horse by the Wichita changed Wichita culture. Hunting bison for the French fur and meat trade became a significant part of the Wichita economy in the 1700s (Wedel, 1981:45). Horses are believed to have made the pursuit and transport of many bison possible for the Wichita.

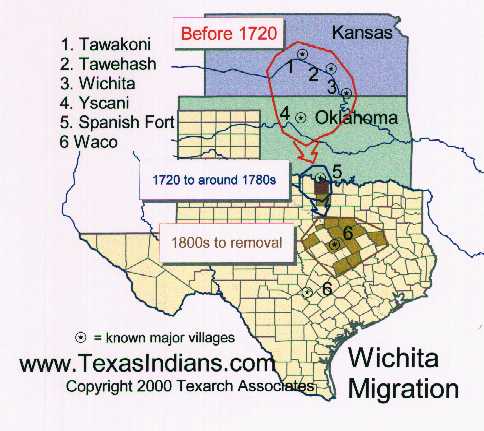

By the middle of the 18th century Tawehash had settled on upper Red river, where they remained for about a hundred years. There is evidence that, instead of draught, other Indians drove the Wichita south after AD 1720. The draught west of the 96th meridian was from AD 1439 till 1540 per Wedel (Bell, 1974:34). The Osage, Chickasaw, and Comanche moved their hunting grounds into the Arkansas River valley. These people’s nomadic culture did not fit with the Wichita semi sedentary and the Wichita people moved to the Red River around Anadarko, Oklahoma.

They moved south about the same time as the Tawakoni and other tribes of the group and were found on Red River in 1759, when they defeated a Spanish force sent against them as mentioned. They remained in this same region until they united as the Wichita. Any descendants are among the Wichita in Oklahoma today.

In 1820, the Wichita, Waco, Tawakoni, Tawehash, and Kichais were estimated at no more than 1400 persons. Although a reservation and agency were established, the Wichita people were not able to remain in this land. In 1863, they were forced by Confederate troops to leave their reservation and move north to Kansas. While in Kansas from 1863 to 1867, the Wichita’s had no land to farm and few friends to help. Some starved, others suffered from smallpox and cholera epidemics. Only 822 Wichita people returned to Indian Territory in 1867. In 1998 there were maybe 10 Tawehash speakers. The Tawehash moved whereever the pressures of civilization pressed them. A map of that movement is attached. They were strong enough in the 16th century to hold off the Spanish. They always had allies among other Indians and even the Europeans then encountered. Today the Tawehash have disappeared as a band of people and all but disappeared from history. They avoided their Mother in laws and never did like the Apache.

Significant and continuing influence of the Wichita name is found in North Texas in the name of a river, the name of a county, and the name of a city, Wichita Falls. Wichita, Kansas, owes its name to the early presence of the tribe in this area. We see Kechi, Kansas and Camp Tawakoni near Wichita carry on those Band names. Obscurity overtook the Tawehash or Taovayas name except in history books.

More on the Wichita by clicking Here References:

Bell, Robert E.; Jelks, Edward B; Newcomb, W.W.

DeMallie, Raymond J.

Fowler, Loretta

Wedel, Mildred Mott

Wedel, Mildred Mott

Winship, George Parker

For photos of the excavation, visit http://www.normconley.info. Archaeologists in Oklahoma have identified a small

number of 17th and 18th century villages in the state where they believe

intensive contact occurred between European and Native American peoples. To

date, however, none of these sites have been thoroughly examined. The

Bryson-Paddock (34KA5) site is located on a bluff overlooking the Arkansas River

near Newkirk, Oklahoma. An earlier generation of archaeologists and historians

determined that Bryson-Paddock served as one of

3 or 4 major ports-of-trade where Wichita Indians

met French trappers/traders from the Arkansas Post near the junction of the

Arkansas and Mississippi rivers. For a number of years in the early to mid 18th

century French entrepreneurs traded with the Wichita bringing European trade

goods to Oklahoma and moving large quantities of meat and hides to New Orleans

with some eventually shipped to Europe. Reports of French traders among the

Wichita also spurred Spanish expeditions into the region, since the latter saw

their own colonial ambitions threatened. French and Spanish explorers documented

their encounters with the Wichita: The Bryson-Paddock site and its sister-site,

Deer Creek (34KA3), came to be called “Ferdinandina” in Spanish and French

documents (Wedel 1988). Thus, the Wichita came to be central players in the

European struggle for the Southern Plains. Excavations at Bryson-Paddock

together with archival research will help us to better understand these complex

historical relations.. While the importance of the Bryson Paddock site has long

been recognized (e.g., Thoburn and Wright 1929; Wedel 1988; Bell 1984), prior

work there did little in terms of addressing many important issues. Was

Bryson-Paddock a Wichita encampment visited by the French or a fortified French

trading post where Wichita brought bison and deer hides to trade? How extensive were the

Wichita fortifications and did they build other earthen features at this

village? For how long was the site inhabited? In terms of chronology, how did

its occupation relate to similar Wichita occupations in Oklahoma, Kansas and

Texas? Finally, and perhaps most importantly, how did this trading partnership

impact the culture and society of the Wichita? The current project thus

represents a special opportunity to address many of the longstanding questions

about early Wichita-French-Spanish interaction and to make a significant

contribution to the early history of Oklahoma. The research is designed to

evaluate the activities that occurred at this large site and identify the extent of French

residence at the village as well as the impact of extensive European contact on

18th century Wichita culture. Students enrolled in the field school will gain

experience in excavation techniques, surveying, remote sensing, and lab

processing. Participants will also learn mapping techniques with a total mapping

station. Other lessons will include archeological photography, profiling,

flotation, and soil identification. Lectures will be presented on Southern

Plains Village prehistory and early Wichita archeology. Field trips may be

scheduled for nearby archeological sites. OU Professor Richard Drass said the Bryson-Paddock

and "Ferdinandina" villages were two important sites for providing information

on the material culture and social culture during a time of change for the

Wichita tribe. Newkirk Herald Journal

Front Page News -

[Cached

Version] "The French would take the buffalo hides, pile them

on a barge and float them down the river to the Arkansas Post at the mouth of

the Arkansas and Mississippi rivers," said Richard Drass, a professor with the

Oklahoma Archaeological Survey housed at OU. Newkirk Herald Journal

Front Page News -

[Cached

Version] OU Professor Richard Drass said the Bryson-Paddock

and Ferdinandina villages were two important sites for providing information

on the material culture and social culture during a time of change for the

Wichita tribe "Before this time early- to mid- 1700s the Wichita themselves

had very little contact with Europeans, other than minimal contact with the

Spanish," Drass said. tulsaworld.com:

News - [Cached

Version] Richard Drass, a state archaeologist with the

Oklahoma Archaeological Survey at the University of Oklahoma, describes part

of an archaeological dig of Wichita Tribe artifacts on the property of Terry

and Karla Cheek northeast of Newkirk. Oklahoma test pit at Bryson-Paddock Interesting History of FRENCH

INTRUSIONS INTO NEW MEXICO 1749-1752 (1 Miss Anne Wendels, a graduate student at the University of

California, has clearly shown that the Panis visited by DuTisnS were on the

Arkansas River southwest of the Osage, and that DuTisne did not, as is sometimes

stated, pass beyond to the Padoucah (Apache). French Interest in and Activities

on the Spanish Border of Louisana, 1717-1753, Ms. thesis. * Miss Wendels, in the

paper cited above, has made a most careful study of the routes of La Harpe on

this and his former expedition, with convincing results. For Bourgmont's route I

follow Miss Wendels, who differs somewhat from Parkman, Heinrich, and others. ) Note: This text is only an excerpt that calls out the visit by

DuTisne to the Panipiquet villages on the Arkansas about 1719. This date

preceeds archaeological evidence at Byson - Paddock and what we know of Deer

Creek sites. The visit may have been the village that was in the vicinity

of Arkansas City at the time.

complete text of French Intrusions into New Mexico 1916 Wichita. A confederacy of Caddoan

stock, closely related linguistically to the Pawnee,

and formerly ranging from about the middle Arkansas river, Kansas, southward

to Brazos river, Texas, of which general region they appear to be the aborigines;

antedating the Comanche,

Kiowa,

Mescaleros,

and Siouan

tribes. They now reside in Caddo County, west Oklahoma, within the limits

of the former Wichita

Reservation. Additional Wichita Indian Resources The books presented are for their historical value only and are not the opinions

of the Webmasters of the site.

1974 Wichita Indians, Wichita Indian Archaeology and Ethnology

2001, Handbook of North American Indians, Plains

Volume 13 Part 1, Smithsonian Institution, Washington

2003, The Columbia Guide To American Indians of the Plains

1981, The Deer Creek Site, Oklahoma: A Wichita Village sometimes

called Ferdinandina, An Ethnohistorian’s view

1988, The Wichita Indians 1531-1750 an Ethnohistorical Essays

1964 (1896) The Coronado Expedition 1540-1542

strong>

Dr. Richard Drass, Oklahoma Archaeological

Survey

Published on: 6/19/2004 Last

Visited: 6/20/2004

"Before this time -- early to mid 1700s --

the Wichita themselves had very little contact with Europeans, other than

minimal contact with the Spanish," Drass said.

Published on: 6/23/2006 Last Visited: 6/23/2006

...

Drass said

the excavation this summer was aimed at providing a "bigger picture" of how

the Indians at Bryson-Paddock

lived."We are looking for the big layout this

time," he said.

Published on: 6/24/2004 Last Visited: 6/26/2004

Published on: 1/8/2007 Last

Visited: 1/8/2007

...

Richard Drass, a

state archaeologist with the Oklahoma Archaeological Survey at OU confirmed

that Cheek's discoveries revealed a remarkable era before Indian Territory was

created.

"We've been able to date this back to between

1720 and 1750," Drass said "We've been able to tell that it had a

fortification for defense, and we can see they were wanting to get into the world economy with the French."

The property's bounty was

by no means a new discovery. The land had been excavated by university groups

and archaeologists since the early 1920s.Drass

said the Bryson-Paddock site was one of the

first officially excavated in Oklahoma. He estimates that the Bryson-Paddock

sites held about 3,000 Wichita's.

Over the decades, it has

continued to reveal new information, with the most recent dig conducted this

summer by Drass and a group of OU archaeology students.

Drass said that at one time, the Wichita's numbered in the

thousands before epidemics and settlement reduced their population. Excavated

Wichita encampments also have been found in central, western and southern

Oklahoma.

Historically, the tribe lived in huge grass

houses that were the rough equivalent of modern split-level condominiums.

"In one of the excavations on this site, remains of a

grass lodge were unearthed that measured 42 feet in diameter," Drass said. "It

could have been the house of a chief or another person of prominence in the

tribe."

...

Drass can point out slight mounds on the land

that look like gentle grassy knolls, but signal the Wichita version of trash

heaps. In one section of land that has never been plowed, archaeologists

unearthed a fortification that protected the tribe from attacks by neighboring

tribes, including the Osage and possibly the Apache.

"The

Osage were pushing down on the Wichita from the Missouri River valley," he

said.

...

Their presence is a telltale sign of an

encampment, Drass said.

"They don't belong there," he

said."That tells us that someone moved them up here from the bluffs for

various purposes."

Charting history

The site has turned up no

human remains. But Drass said magnetometers may

help scientists uncover more exact details.

...

Glass beads,

copper and other trade items have been found turned, Drass said.

...

Drass said archaeological work will continue on the

site. The Cheeks' findings and their excavations have helped to paint a more

accurate picture of one of the state's earliest inhabitants, Drass said.

"What we found out here showed us it was a lot different

than what we thought life was like for this tribe," he said.

"BY HERBERT E. BOLTON

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA

BANCROFT LIBRARY

REPRINTED FROM "THE PACIFIC OCEAN IN HISTORY"

BY H. MORSE STEPHENS AND HERBERT E. BOLTON.

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY, PUBLISHERS, NEW YORK

Copyright, 1917, By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

EARLY in the eighteenth century French voyageurs, chasseurs, and traders of

Louisiana and Canada looked with covetous eyes toward New Mexico. To the

adventurer it was a land promising gold and silver and a path to the South Sea ;

to the merchant it offered rich profits in trade. The three natural avenues of

approach to this Promised Land were the Missouri, Arkansas, and Red rivers. But

there were two obstacles to expeditions bound for New Mexico. One was the

jealous and exclusive policy of Spain which made the reception of such Frenchmen

as might reach Santa Fe a matter of uncertainty ; the other was the Indian

tribes which stood in the way. The Red River highway was effectually blocked by

the Apache, mortal enemies of all the tribes along the lower valley; the

Arkansas and Missouri River avenues were impeded by the Comanche for analogous

reasons. It was not so much that the Apache and Comanche were averse to the

entrance of French traders, as that the jealous enemies of these tribes opposed

the passage of the traders to their foes with supplies of weapons. It is a

matter of interest that in the nineteenth century the American pioneers found

almost identical conditions in the same region.

As the fur traders and official explorers pushed rapidly west, one of their

constant aims was to open the way to New Mexico by effecting peace between the

Comanche and the tribes further east. In 1718-1719 La Harpe

ascended the Red River and established the Cadodacho post ; Du Rivage

went seventy leagues further up the Red River; and La Harpe crossed over to the

Touacara villages on the lower Canadian. At the same time DuTisne

reached the Panipiquet, or Jumano, villages on the Arkansas, north of the

Oklahoma line. Finding further advance cut off by the hostility of the

Jumano for the Comanche, he tried, but without avail, to effect a treaty between

the tribes. 1 Two years later La Harpe reestablished the Arkansas post, ascended

the river half way to the Canadian, and urged a post among the Touacara, as a

base for advance to New Mexico. 2 In 1723 Bourgmont erected a post among the

Missouri tribe to protect the fur traders there, to check an advance by the

Spaniards such as had been threatened by the Villazur expedition in 1720, and as

a base for commerce with New Mexico. To open the way thither he led Missouri,

Kansas, Oto, and Iowa chiefs to the Padoucah (Comanche), near the Colorado

border of Kansas, effected a treaty between them, and secured permission for

Frenchmen to pass through the Comanche country to the Spaniards. 3

Shortly afterward the Missouri post was destroyed by Indians, the Missouri

valley was made unsafe for a number of years by the Fox wars, and French advance

westward was checked. Although there are indications that in the interim traders

kept pushing up the Missouri, the next well known attempt to reach New Mexico

was made in 1739. In that year the Mallet party of eight or nine men left the

Missouri River at the Arikara villages, went south to the Platte River, ascended

that stream, and made their way through the Comanche country to Taos and to

Santa Fe. After being detained several months in friendly captivity, six or

seven of the party returned, unharmed by the Spanish authorities, and bearing

evidence that the residents of New Mexico would welcome trade. Four of the party

descended the Canadian and Arkansas rivers, the others going northeast to the

Illinois.

The Mallet party had succeeded in getting through the Comanche country to New

Mexico and had returned in safety and with good prospects for trade two

important achievements. Immediately there was renewed interest in the Spanish

border,

on the part of both government officials and of private adventurers. At once, in

1741, Governor Bienville sent Fabry dela Bruyere, bearing a letter to the

governor of New Mexico ana guided by four members of the Mallet party, with

instructions to retrace the steps of the latter, open up a commercial route, and

explore the Far West. 1 Shortly afterward a new military post, called Fort

Cavagnolle, was established on the Missouri at the Kansas village, and the

Arkansas route was made safe by effecting in 1746 or 1747 a treaty between the

Comanche and the Jumano.

The effect of the treaty was immediate, and at once there were new expeditions

to New Mexico by deserters, private traders, and official agents. The fact that

they occurred has only recently come to light. The incidents are so unknown to

history, and reveal so many important facts concerning the New Mexico- Louisiana

frontier, that they deserve narration, and have therefore occasioned this paper.

Their records are contained in two expedientes in the archives of Mexico,

discovered by the present writer. 2

Before proceeding to the narration of these intrusions, a word further must be

said regarding the position of the Comanche on the Spanish border. At that time

the tribe roamed over the plains between the upper waters of the Red River and

the Platte, the two divisions most frequently mentioned being the Padoucah and

the Laitane, or Naitane. They followed the buffalo for a living and had large

droves of horses, mules, and even burros,

1 Lettre de MM. Bienville et Salmon, April 30, 1741, in Margry, Decouvertes,

vol. 4, pp. 466-467; Instructions donnees & Fabry de la Bruyere, ibid., pp.

468-470; Ex- trait des lettres du sieur Fabry, a r occasion du voyage projetes a

Santa Fe, ibid., pp. 472-492; Wendels, French Interests and Activities on the

Spanish Border of Louisiana, 1717-1753. After proceeding a short distance up the

Canadian, Fabry was forced through lack of water for canoes to go back to the

Arkansas post for horses. Returning, by way of the Cadodacho, he found that the

Mallet brothers had continued toward Santa Fe, on foot. Giving up the project,

Fabry crossed over from the Canadian to the Red River, where he

visited the Tavakanas and Kitsaiches (Towakoni and Kichai), two of the tribes

which La Harpe had found on the Canadian in 1719. The further adventures

of the Mallets have not come to light, but it is known that in 1744 a Frenchman

called Santiago Velo reached New Mexico. He was secretly despatched to Mexico by

Governor Codallos y Rabal. Twitchell, R. E., The Spanish Archives of New Mexico,

vol. 1, p. 149. "

The name Wichita, by which they are commonly known, is of uncertain origin and

etymology. They call themselves Kitikiti'sh (Kirikirish), a name also of uncertain

meaning, but probably, like so many proper tribal names, implying preeminent

men. They are known to the Siouan tribes as Black Pawnee (Paniwasaba, whence

"Paniouassa," etc.), to the early French traders as Pani Piqué,

'Tattooed Pawnee,' to the Kiowa and Comanche by names meaning 'Tattooed Faces,'

and are designated in the sign language by a sign conveying the same meaning.

They are also identifiable with the people of Quivira met by Coronado in 1541.

The Ouachita

living in east Louisiana in 1700 are a different people, although probably of

the same stock.

Among the tribes composing the confederacy, each of which probably spoke a slightly

different dialect of the common language, we have the names of the Wichita proper

(?), Tawehash (Tayovayas), Tawakoni

(Tawakarchu), Waco,

Yscani, Akwesh, Asidahetsh, Kishkat, Korishkitsu. A considerable parts of the

Panimaha, or Skidi Pawnee, also appear to have lived with them about the middle

of the 18th century, and in fact the Pawnee and Wichita tribes have almost always

been on terms of close intimacy. It is possible that the Yscani of the earlier

period may be the later Waco (Bolton). The only divisions now existing are the

Wichita proper (possibly synonymous with Tawehash), Tawakoni, and Waco. To these

may be added the incorporated Kichai remnant, of cognate but different language.

Just previous to the annexation of Texas to the United States, about 1840-5,

the Tawakoni and Waco resided chiefly on Brazos river, and were considered as

belonging to Texas, while the Wichita proper resided north of Red river, in

and north of the Wichita mountains, and were considered as belonging to the

United States. According to the best estimates for about 1800, the Wichita proper

constituted more than two-thirds of the whole body.

The definite history of the Wichita more particularly of the Wichita proper

begins in 1541, when the Spanish explorer Coronado entered the territory known

to his New Mexican Indian guides as the country of Quivira. There is some doubt

as to their exact location at the time, probably about the great bend of the

Arkansas river and northeastward, in central Kansas, but the identity of the

tribe seems established (consult Mooney in Harper's Slag., June 1899; Hodge

in Brower, Harahey, 1899). On the withdrawal of the expedition after about a

month's sojourn the Franciscan father Juan de Padilla, with several companions,

remained behind to undertake the Christianization of the tribe, this being the

earliest missionary work ever undertaken among the Plains Indians. After more

titan three years of labor with the Wichita he was killed by them through jealousy

of his spiritual efforts for another tribe.

In 1719 the French commander La Harpe visited a large camp of the confederated

Wichita tribes on South Canadian river, in the eastern Chickasaw Nation, Oklahoma,

and was well received by them. He estimated the gathering, including other Indians

present, at 6,000 souls. They had been at war with another tribe and had taken

a number of prisoners whom they were preparing to eat, having already disposed

of several in this way.

They seem to have been gradually forced westward and southward by the inroads

of the Osage

and the Chickasaw to the positions on upper Red and Brazos rivers where they

were first known to the Americans. In 1758 the Spanish mission and presidio

of San Sabá, on a tributary of the upper Colorado river, Texas, were

attacked and the mission was destroyed by a combined force of Comanche, Tawakoni,

Tawehash, Kichai, and others. In the next year the Spanish commander Parilla

undertook a retaliatory expedition against the main Wichita town, about the

junction of Wichita and Red rivers, but was compelled to retreat in disorder,

with the loss of his train and field guns, by a superior force of Indians well

fortified, and armed with guns and lances and flying the French flag. In 1760

the confederated Wichita tribes asked for peace and the establishment of a mission,

and on being refused the mission, renewed their attacks about San Antonio. In

1765 they captured and held for seine time a Spaniard, Tremiño, who has

left a valuable record of his experiences at the main Tawehash town on Red river

In 1772 the commander Mezières visited them and other neighboring tribes

for the purpose of arranging peace. From his data the Tawakoni, in two towns

on Brazos and Trinity rivers, may have had 220 warriors, the "Yscanis"

(Waco?) 60, and the Wichita proper and "Taovayas" 600, a total of

perhaps 3,500, not including the Kichai. In 1777-8 an epidemic, probably smallpox,

swept the whole of Texas, including the Wichita, reducing some tribes by one-half.

The Wichita, however, suffered but little on this occasion. In the spring of

1778 Mezicres again visited them, and found the Tawakoni (i. e. the Tawakoni

and Waco) in two towns on the Brazos with more than 300 men, and the Wichita

proper in two other towns on opposite sides of Red river (below the junction

of Wichita river), these last aggregating 160 houses, in which he estimated

more than 800 men, or perhaps 3,200 souls. The whole body probably exceeded

4,000. (H. E. Bolton, inf'n, 1908.)

In 1801 the Texas tribes were again ravaged by smallpox, and this time the Wichita

suffered heavily. In 1805 Sibley officially estimated the Tawakoni (probably

including the Waco) at 200 men, the "Panis or Towiaches" (Wichita

proper) at 400 men, and the Kichai at 60 men, a total of about 2,600 souls,

including the incorporated Kichai. An estimate by Davenport in 1809 rated the

total about 2,800. A partial estimate in 1824 indicates nearly the same number.

At this time the Waco town was on the site of the present Waco, while the Tawakoni

town was on the east side of the Brazos above the San Antonio road. From about

this time, with the advent of the Austin colony, until the annexation of Texas

by the United States, a period of about 25 years, their numbers constantly diminished

in conflicts with the American settlers and with the raiding Osage from the

north.

In 1835 the Wichita proper, together with the Comanche, made their first treaty

with the Government, by which they agreed to live in peace with the United States

and with the Osage and the immigrant tribes lately removed to Indian Territory.

In 1837 a similar treaty was negotiated with the Tawakoni, Kiowa, and Kiowa

Apache (Ta-wa-ka-ro, Kioway, and Ka-ta-ka, in the treaty). At this time, in

consequence of the in roads of the Osage, the Wichita had their main village

behind the Wichita mountains, on the North fork of Red river, below the junction

of Elm fork, west Oklahoma. In consequence of the peace thus established they

soon afterward removed farther to the east and settled on the present site of

Ft Sill, north of Lawton, Oklahoma; thence they removed about 1850 still farther

east to Rush Springs. The Tawakoni and Waco all this time were ranging about

the Brazos and Trinity rivers. in Texas. In 1846, after the annexation of Texas,

a general treaty of peace was made at Council Springs on the Brazos with the

Wichita proper, Tawakoni, and Waco, together with the Comanche, Lipan, Caddo,

and Kichai, by which all these acknowledged the jurisdiction of the United States.

In 1855 the majority of the Tawakoni and Waco, together with a part of the Caddo

and Tonkawa, were gathered on a reservation on Brazos river westward from the

present Weatherford. In consequence of the determined hostility of the Texans,

the reservation was abandoned in 1859, and the Indians were removed to a temporary

location on Washita river, Okla. Just previous to the removal the Tawakoni and

Waco were officially reported to number 204 and 171 respectively. In the meantime

the Wichita had fled from the village at Rush Springs and taken refuge at Ft

Arbuckle to escape the vengeance of the Comanche, who held them responsible

for a recent attack upon themselves by United States troops under Major Van

Dorn (1858). The Civil War brought about additional demoralization and suffering,

most of the refugee Texas tribes, including the Wichita, taking refuge in Kansas

until it was over. They returned in 1867, having lost heavily by disease and

hardship in the meantime, the Wichita and allied tribes being finally assigned

a reservation on the north side of Washita river within what is now Caddo County,

Okla. in the next year they were officially reported at 572, besides 123 Kichai.

In 1902 they were given allotments in severalty and the reservation was thrown

open to settlement. The whole Wichita body numbers now only about 310, besides

about 30 of the confederated Kichai remnant, being less than one-tenth of their

original number.

Like all tribes of Caddoan stock the Wichita were primarily sedentary and agricultural,

but owing to their proximity to the buffalo plains they indulged also in hunting

to a considerable extent. Their permanent communal habitations were of conical

shape, of diameter from 30 to 50 feet, and consisted of a framework of stout

poles overlaid with grass thatch so as to present from a short distance the

appearance of a haystack. Around the inside were ranged the beds upon elevated

platforms, while the fire-hole was sunk in the center. The doorways faced east

and west, and the smoke-hole was on one side of the roof a short distance below

the apex. Several such houses are still in occupancy on the former reservation.

There were also drying platforms and arbors thatched with grass in the same

way. The skin tipi was used when away from home. The Wichita raised large quantities

of corn and traded the surplus to the neighboring hunting tribes. Besides corn

they had pumpkins and tobacco. Their corn was ground upon stone metates or in

wooden mortars. Their women made pottery to a limited degree. In their original

condition both sexes went nearly naked, the men wearing only a breech-cloth

and the women a short skirt, but from their abundant tattooing they were designated

preeminently as the "tattooed people" in the sign language. Men and

women generally wore the hair flowing loosely. They buried their dead in the

ground, erecting a small framework over the mound.

The Wichita had not the clan system, but were extremely given to ceremonial

dances, particularly the picturesque "Horn dance," nearly equivalent

to the Green Corn dance of the Eastern tribes. They had also ceremonial races

in which the whole tribe joined. Within recent years they have taken up the

Ghost dance and Peyote rite. Their head-chief, who at present is of Tawakoni

descent, seems to be of more authority than is usual among the Plains tribes.

In general character the Wichita are industrious, reliable, and of friendly

disposition.

Handbook of American Indians, 1906